It’s more than 50 years since the first Landsat mission was launched, and in half a century a series of nine satellites have beamed back scientifically valuable and visually stunning images of our planet’s surface.

However, when clouds obscure the Earth (as they frequently do), the images have been considered useless and left to gather dust in the archives.

Now, an innovative new approach, led by 2020 Schmidt Science Fellow Jacqueline Campbell, is utilizing AI to sift through abandoned data and garner fresh insights in our understanding of clouds and their contribution to climate change.

Clouds Decoded is funded by the Advanced Research + Invention Agency, the UK funding agency established to empower researchers to think differently.

“Today’s satellites can gather as much data on one sensor in one day as an entire multi-year mission in the 1970s. This volume of data is impossible to process by hand and AI is a crucial tool for recognizing patterns and finding meaning within vast volumes of data,” explained Dr. Campbell.

Combining AI with traditional data analysis techniques, Dr. Campbell, Alistair Francis, and Mikolaj Czerkawski have started to sift through millions of cloudy images from the Sentinel-2 satellite, a European modern counterpart to Landsat.

But they don’t just leave it all to AI. “We work with experts to ensure that the AI analysis is very focused and targeted,” said Dr. Campbell.

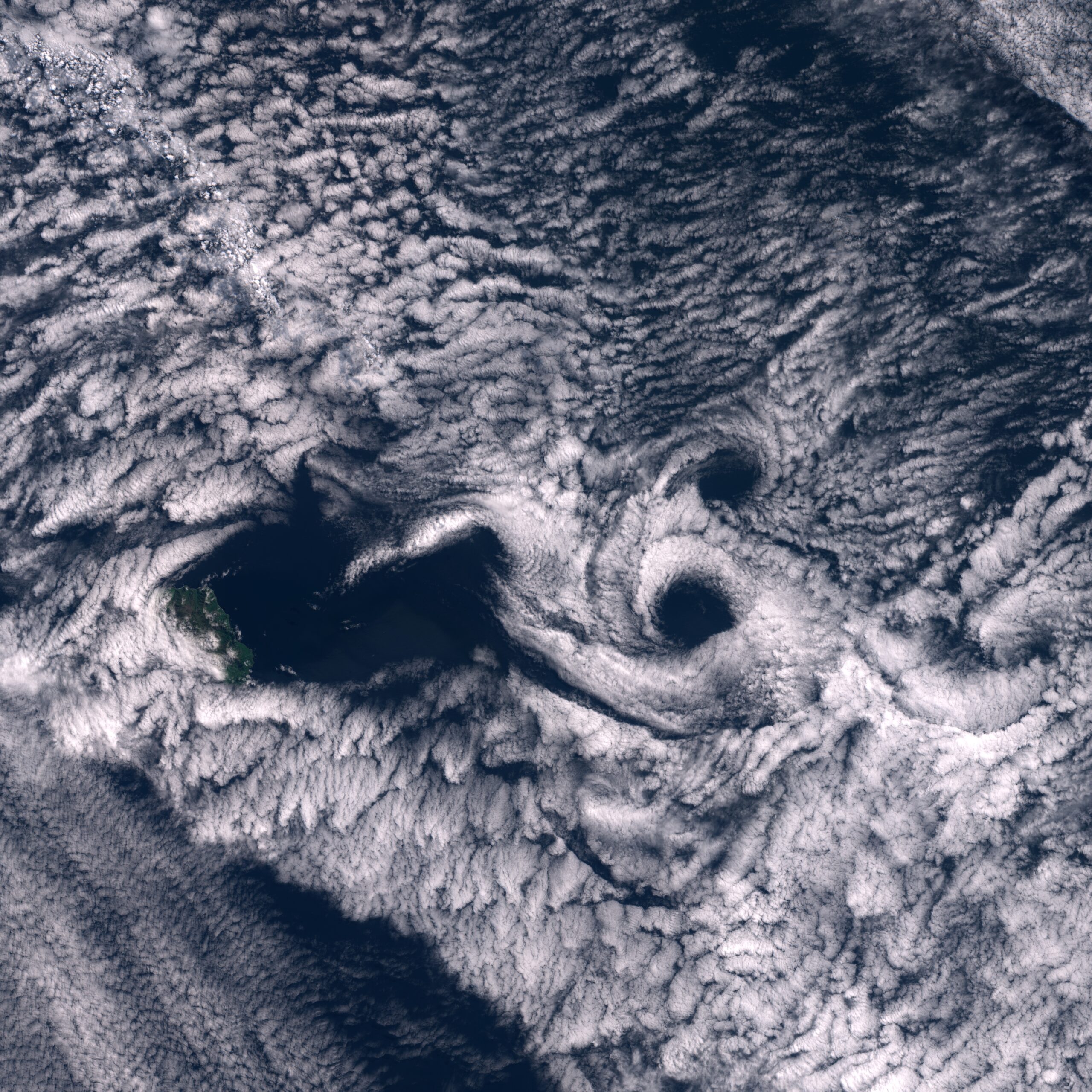

And the team are homing in on ‘mixed phase’ clouds; those that contain both water and ice.

Ice and water crystals reflect light in different ways and the ratio of ice to water in a cloud is thought to be a crucial factor in whether it is a cloud that traps heat and causes warming or reflects solar radiation and causes cooling.

The team is exploiting this difference to train the AI to categorize different types of cloud in the Sentinel 2 images. The project is monitoring how clouds move between liquid and ice phase and how rising global temperatures may affect these transitions – something that is currently not well understood but could have huge implications for the speed at which our planet warms in the future.

For Dr. Francis and Dr. Czerkawski, it is a significant pivot. They spent years removing clouds from satellite images, in order to see the land, but over time their interest was piqued by the stunning cloud images they were discarding. “We realized that the diversity we could see in the images described physical differences in the cloud,” said Dr. Francis.

Dr. Czerkawski said advancing technology is helping to unlock these insights: “These satellites were not designed to monitor clouds, but AI provides us with new ways of extracting useful information without having to invest in new satellites and sensors.”

And it is not just the science that is innovative. To support their work, the trio has established Asterisk Labs, the UK’s first worker-owned cooperative research laboratory.

Setting up an independent lab has freed them from the short-term contracts and constraints of a traditional academic setting. They have developed a co-operative model where everyone takes collective responsibility for decision making in the lab.

They are committed to open science, to maximise social and scientific benefit, and enable people from all walks of life to get involved, something that is particularly close to Dr. Campbell’s heart.

“I came from a working-class background and was always interested in Space, but never felt that science was for people like me,” she explained. After leaving school, she worked as a train driver on the London Underground for more than ten years, but eventually took the plunge and signed up for an Open University correspondence course in high school maths and science.

That was the hook that ultimately led her to a PhD researching life on Mars, at the Mullard Space Science Labs at University College London. “I loved space science but at the end of the PhD asked myself, ‘even if I did find bacteria on Mars, what difference does it make’?”

A Schmidt Science Fellowship enabled Dr. Campbell to pivot into oceanography and climate science. “The Fellowship allowed me to take a risk – that’s one of the things I really love about it. And it introduced me to a whole different community of people from a wide range of disciplines and appreciate the value of interdisciplinarity in science,” she explained.

The connections she made during her fellowship led to her working in a science startup, and gaining valuable skills in setting up a business.

“It’s been invaluable to be part of such a wonderful, diverse community like Schmidt Science Fellows. We have been able to draw on the expertise of other Fellows who are atmospheric physicists, aerosol spectroscopists, and mathematicians, who all understand the value of interdisciplinary approaches, as well as get advice on setting up a new lab, and thinking through our vision,” said Dr. Campbell.

“The incredible support from the Schmidt Science Fellows team has really helped us to make connections across the scientific ecosystem and start something truly special.”

Launching Asterisk Labs with Francis and Czerkawski and starting the Clouds Decoded project has come out of the culmination of all of these experiences. “I feel like it’s been forty years in the making and I’m now finally doing the thing I really wanted to do,” she said.

Main Image: Cloud formations above Gough Island, South Atlantic. Copernicus Sentinel Data, 2025, modified by Asterisk Labs.