Dr Fred Richards is a 2018 Schmidt Science Fellow who is passionate about strengthening the role of scientific evidence in policymaking. As a geophysicist who moved to Harvard University to study prehistoric sea-levels to better understand the potential impact of climate change on coastal communities, he is especially interested in the role of science in the formulation of energy and climate policies.

For me, a major bonus of the Schmidt Science Fellow experience has been our exposure to the world of public policy during the Global Meetings. I think our cohort all believe that innovative, scientifically informed policymaking will be just as important as developing technology in meeting the increasingly complex challenges humanity faces. However, I also think that we, like many scientists, share a certain trepidation about wading into the policymaking arena. Our training tends to make us didactic and perfectionist; we are always looking for the absolutely correct answer; whereas politics is the art of low compromise for the greater good. As the saying goes: “To retain respect for laws and sausages, one must not watch them in the making.”

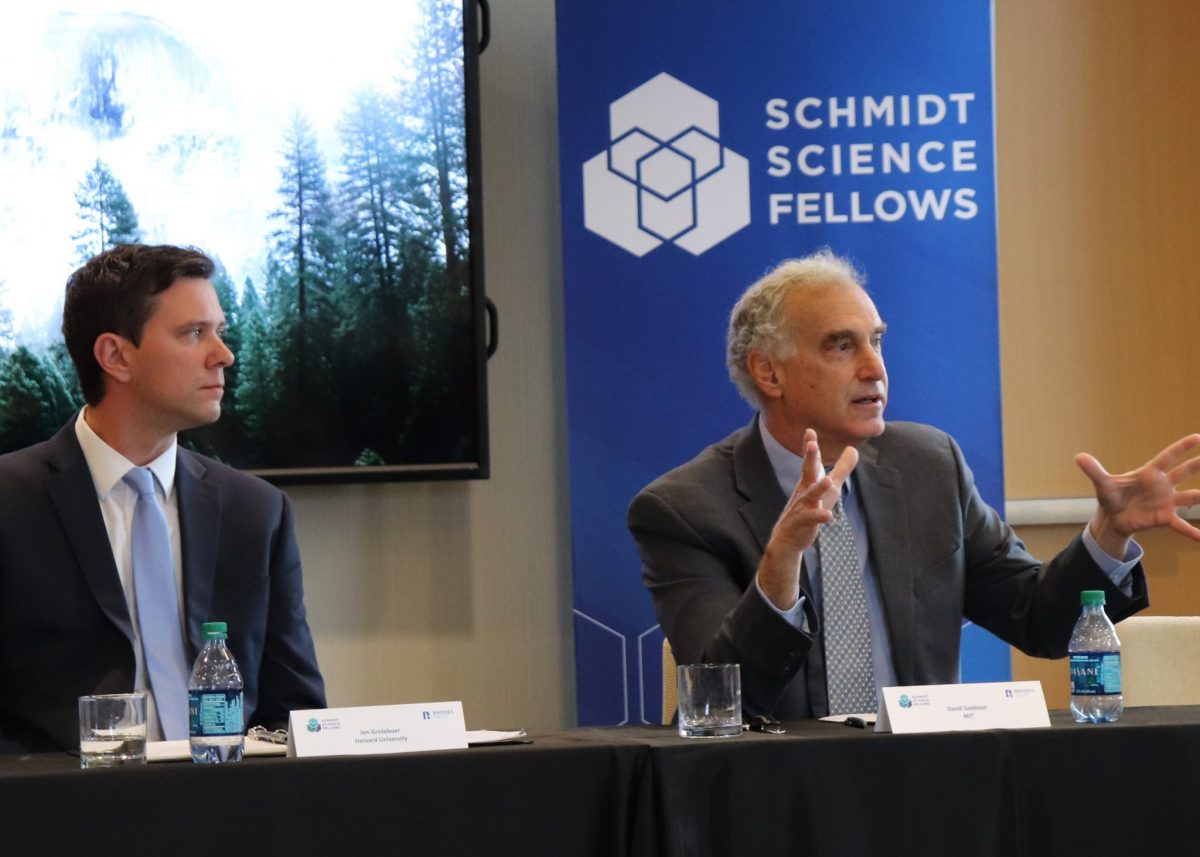

Thankfully, a number of thoughtfully crafted sessions spread across the Global Meetings have helped to demystify the policymaking process, and made the prospect of getting involved far less daunting. During an inspirational day at the Blavatnik School of Government in Oxford, we were given a flavor of how and why policymakers make decisions, why they do not always listen to scientific advice, and what strategies we might implement to ensure that we are heard. At the University of Cambridge, we then learned how best to communicate scientific concepts and data to policymakers; we then had the opportunity to craft our own policies and pitch them to former ministers. Finally, during sessions hosted by MIT and Harvard, we heard from scientists who had successfully made the transition into public policy, including senior members of President Obama’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, a former director of the CIA, and a former US Secretary of Energy.

The opportunity to interact with such experienced and accomplished individuals was invaluable; I have come away feeling much clearer about what steps I will take to participate in the policymaking process, how the levers of power operate, and where scientific advisors fit into that machinery.

Throughout these sessions, I was struck by a number of recurring themes. First, in politics, timing is everything. Governments have a limited lifespan and bandwidth, meaning that politicians, irrespective of the weight of scientific evidence, are unlikely to champion a cause unless they can be sure it will have strong and broad public support. Scientists therefore need to be influential both with policymakers and the public. Keeping an ear to the ground – and making your case only when you think lawmakers might be willing to listen – seems to be crucial.

Second, at the risk of stating the obvious, policymakers want solutions not problems. It is not enough to highlight areas where science suggests the need for policy change; having a well-thought-out proposal for what the response should be will increase the odds that the evidence will be properly considered.

Third, as scientists, we have a duty to serve society. Providing advice to government, when called upon, should be considered an integral part of that responsibility. I think many scientists are squeamish about being pulled into policy debates for fear of their objectivity being questioned. The recent polarization and politicization of climate science has given some legitimacy to that anxiety. However, given that doubts about the validity of science seem to be in vogue in some political circles and on social media, the argument for researchers to actively engage with policymakers, and in the public debate more generally, has seldom been more compelling.

It is clear that, in most countries, the pipeline between academic research and government policy is leaky. I had previously assumed that politics was the root of the problem; an inevitable consequence of the scarcity of scientifically-trained politicians and civil servants. The Global Meeting sessions have made it clear to me that scientists are also culpable.

Phrases such as “politics is the art of the possible” and “don’t let the best be the enemy of the good” may offend my left-brained sensibilities but in government there is usually no single perfect solution for any issue. The political decision-making process is complex, requiring a number of competing interests to be balanced. Scientific evidence is only ever one of the factors to be weighed and, however compelling, it may not, from a practical perspective, be the most decisive. If we want to see more evidence-based policymaking the onus is on us, as scientists, to recognize this fact and communicate our findings more effectively to policy professionals, bearing in mind their need to manage budgets, keep the public onside and fulfill manifesto pledges.

Although there is still much work to do to improve communication between the realms of science and public policy, I was heartened by two key messages to come out of the Global Meetings. First, among American respondents, “hope” is the word most strongly associated with “science”. Second, the vast majority of politicians respect the opinions of academic researchers and want to hear more from them. These are reasons to be optimistic and, armed with the knowledge gained over the past few months, I feel confident that the Schmidt Science Fellows will make telling contributions to future policy discussions. Who knows, some of us may even answer the appeal of one speaker, Dan Schrag, for more scientists to run for office. Watch this space.

All opinions expressed in this article are those of the author.